Weaving a Romanian Fashion Industry from E-trash

This piece was originally written in June 2022.

Alexandra Sipa talks lace-making from electronic waste, developing the creative scene in her native country and decentralising fashion capitals.

Fashioning intricate lace confections from discarded electrical wires, Alexandra Sipa’s work is about polarities. Her 2020 graduate collection, Romanian Camouflage, was inspired by the contrast between austerity and extreme femininity in her home country. Huge, concrete buildings from the Soviet era, now falling apart, form the backdrop for Romania’s glamorous women. “Every single woman on the street has this incredible personal style. Full face of make-up, hair done. You’re not going to see people in their sweatshirts buying groceries.” The eclectic landscape of her native country also follows this idea of contrasts, with Communist buildings sat alongside modern skyscrapers, Turkish and French architecture next to centuries-old Romanian houses. Even the darkness of the Communist period versus the “explosive, loud, colourful, kitschy” Romanian spirit follows this duality.

Sipa did not always have this appreciation for her culture, internalising shame derived from xenophobic Western narratives about Romanians. Wanting to bury her culture and assimilate, when Sipa moved to the UK in 2015 she had a very definitive idea of, “I’m never coming back.” After 6 years abroad and learning about her country’s history, however, “I felt insanely embarrassed that I’d ever felt ashamed of my culture.” By the time she got to her final year, Sipa allowed herself to be proud of her culture and explore it in her design work. “It started with my grandma and the way she treasures everything, turning anything she buys from thrift stores or fairs into these treasures that decorate her house.”

Using wires gleaned from recycling centres, Facebook Marketplace, construction workers and her mum’s electrician back in Romania, Sipa adapted existing lace techniques for her unconventional material. One method of wrapping a wire around another wire is similar to “a Romanian way of crocheting little flowers on doilies. The lacemakers would sew on top of other fabric lace.” Most commonly, she uses a bobbin lacemaking technique with pins and a foam board. Experimenting with the broken cables in her room, this process was discovered as part of a sustainability project in her second year at Central Saint Martins.

The process of making the garments starts off like any other. Sipa makes a toile to first get the shape that she wants, then makes the lace around the clothing patterns. She uses long wires so that she rarely has to replace them and can create a continuous piece. It’s painstaking work, with just the mini-skirt from her latest collection taking a month to create. Joining the respective pieces of the garment together takes about a week. The finishing process requires care, otherwise the wires will be “really harsh on the skin”. Sipa makes a bias binding to cover the ends of the wires and then hammers it. “That’s how everything gets hidden.” It took time to figure out this process, with solutions to problems often creating new designs. Like the bow-adorned bra in her latest collection: initially the bows were a way of hiding the ends of wires if she made a mistake.

The larger pieces get heavy: “I can’t wear them for more than 20 or 30 minutes.” And it’s no surprise. Sipa doesn’t usually keep track of how many wires she uses, but for a custom gown created for the 2021 British Fashion Awards, she counted over 210 strands, each about 2 metres in length. (And that was just for a wire bodice.) Different thicknesses of alarm and internet cables are used for different effects. Due to their pliable nature, the pieces tend to get squashed when being loaned for things like photoshoots and have to be re-moulded. Though the wire dresses are more showpieces, the bras are definitely wearable. Wearing them out over shirts, she compares them to a corset. She also creates floral jewellery from the cables.

Wires feature less heavily in her latest collection, Uncertain Kings, partly because the weaving process gives her calluses on her fingers. “They disappear after a few weeks, but I know that when I get them I really have to stop. I think a friend of mine who did an actual lacemaking course in Italy told me that lacemakers don’t work more than two or three hours a day.” At some points Sipa was doing it for 10 hours a day. “So, me choosing to do that for my final collection was quite stupid health-wise. But I guess a lot of the things we do at CSM are really stupid health-wise,” she laughs. Despite the toll on her hands, the process is “super calming”. “It’s a mental break. I catch up on all of my shows while I’m doing this.”

Previous collections Romanian Camouflage and Sour Floral both had a strong focus on sustainability. She still repurposes electrical waste, works with thrifted materials and buys surplus fabric from factories. (She believes working with limited materials, whether for financial or environmental reasons, is more fun anyway, since it feels more personal. It’s not for nothing that her graduate collection ended up costing her around £2,000 as opposed to the generally quoted figure of £10,000.) However, she explains her shift in thinking: “In a cynical way, it feels like sometimes what you’re doing is a bit useless in terms of actual environmental impact. But where I think you can make a difference is in social sustainability.” For Sipa, this means “going back to your community and trying to create something locally. Instead of everyone flocking to London or Paris or New York. I feel like that could be more exciting than having this one place of concentrated talent and wealth.”

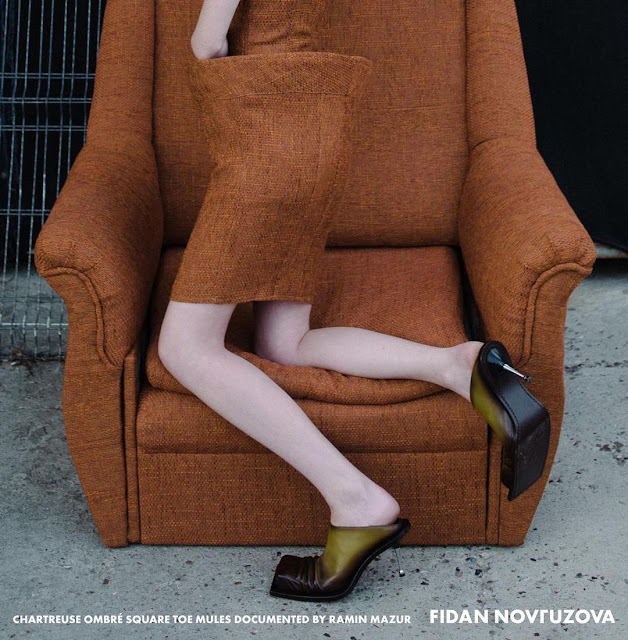

From her apartment in Bucharest, Sipa talks about dismantling the narrative that you must move abroad to pursue a fashion career, “I guess I’m trying to reach out to people who were like me before, who didn’t understand that you can achieve things here as well.” She cites other Eastern European designers like Fidan Novruzova, who is based in Chisinau, Moldova. Ukrainian designer Masha Popova, too, was based in Kyiv until the invasion forced her to move back to London. “We’re one of the first generations, to be honest, to come back home.” Even people a few years older than her have expressed a lack of desire to come back. But Sipa and others are keen to return and stay in Romania, and still work abroad sometimes. She likes to call it being a “remote immigrant”: “you earn your money in maybe more prosperous countries, but you live in places that need more influx of money.” It’s fulfilling to be “building something from the ground up” with other friends that are doing the same thing.

Not only was moving back to Romania a decision to nurture her homeland’s creative industry, it was also a practical one to stay out of debt. Of the mainstream fashion capitals, London is known as somewhere that embraces and supports upcoming designers, allowing young artists to thrive. However, Sipa spoke about how this is increasingly becoming a myth due to extortionate living costs. “You're spending all your money on living instead of on experimenting or on paying other people to work with. Seeing my money go on rent was pissing me off.” And Sipa was still fortunate to have received scholarships and awards. In the past there was more of an option to experiment, fail and try again, whereas now the extreme rents put an immense financial pressure on young artists.

Sipa argued that fashion capitals have very recently become outdated as “COVID made everything possible remotely.” She mentions a slight generational divide, with some older people still preferring the face-to-face route. “They’re like, ‘But why aren’t you coming in person? Just fly to London.’ For a 20-minute meeting that could be on Zoom.” This raises the question: is the relevance of fashion capitals waning? Will other young people head in this direction, when a lot of work can be done online? There are benefits to living around a nucleus of fashion, but social media provides a similar opportunity for networking. With the cost of living only rising, there’s an argument for living somewhere affordable over somewhere fashionable.

“Everything is just so much slower and nicer now. I have a cat,” continues Sipa on the topic of moving back to Romania. “I felt like I had no memories in a way, because my entire life from when I woke up to when I went to sleep was work. I didn’t have any hobbies. I could barely meet anyone.” This links to a larger conversation about the mental stresses of fashion and other creative industries where constant work is normalised and burnout is common. “I’m happy that I broke away from that. I feel like the pressure is getting so horrible in London that I don’t understand why more people are not actually leaving for a place that allows them to… I don’t know, just have a better life.” The toll of “hustle culture” and being chewed up and spat out by the world of work is something that Sipa touches on in her new collection, “as well as just putting yourself in comfortable places to start healing yourself mentally.”

Sipa allowed herself to take her time with this newest collection. Released just recently, she started work on it over a year ago. Partly, this came from a practical need to pause her personal work and do paid projects on the side. “To be financially viable you have to take those projects, be it consulting in fashion design, or custom orders,” explained Sipa. She gave herself time to experiment and edit as much as she wanted, whereas previously, if something didn’t turn out exactly right straight away, “it would send me into this horrible thought process.” Sipa seems much happier now. The period after graduation is a very confusing one, according to the designer. Taking advice from all around and trying to please everyone dominated her process. “I was so obsessed with working so fast and so hard, that I didn’t enjoy designing at all the way I do now.”

Sipa has chosen an alternative path: escaping the financial and work pressures of the London fashion industry in favour of a slower, happier life; turning e-trash into stunning works of art and working to build up Romania’s fashion scene rather than joining an established system. “It just feels a lot more exciting to know that you’re at the beginning of something rather than following the exact same path for success that everyone would follow.”

Sarika Patel struggled to find photogenic keepsake hangers to hold her wedding dress. Custom Wedding Hangers

ReplyDeleteCouples Therapist assist in rekindling emotional and physical intimacy, reigniting passion.

ReplyDelete